Create unlimited customized ACT® Reading practice tests with hundreds of exam-level questions, because if practice feels like the actual exam, then the real thing will feel like practice.

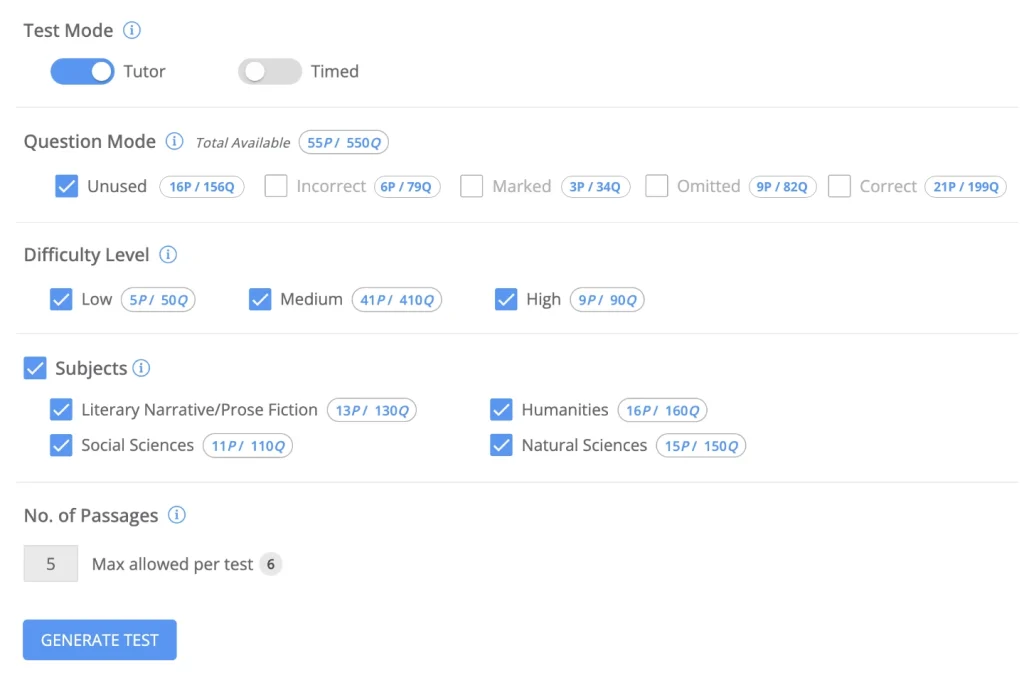

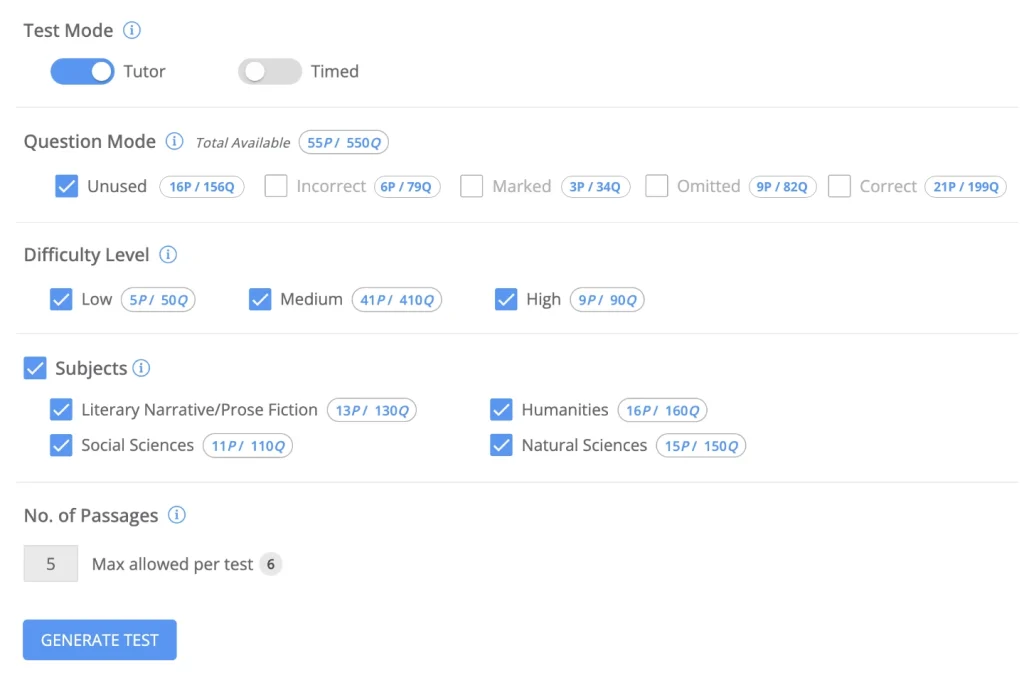

Set up custom tests to hone in on your weaknesses and turn them into strengths with our "Create Test" feature.

Our team of experts writes detailed rationales for each answer choice so you can learn why you got an answer right or wrong.

UWorld’s ACT Reading questions mirror the actual exam in both format and difficulty. Not getting something? Our visual aids and in-depth answer explanations make hard stuff easy to understand. Try it out for yourself…

Select a Question sample.

Eyes focused on the sidewalk, people often observe other people’s shadows and how they interact with one another. What happens when you move closer together? Further apart? How do the shadows change as the Earth’s rotation changes the sun’s position in the sky? Sometimes, one shadow’s magnitude is so great that it swallows up the surrounding shadows so that one cannot tell each apart.

Most vague shadows eventually become more distinct and clearly defined as we look at them more closely, like the lasting impressions of Michelangelo, Botticelli, and el Greco’s Renaissance paintings. But what of the shadows that are swallowed up by another’s magnitude? Such is the relationship between da Vinci and his pupil Francesco Melzi. Melzi was born around 1491, approximately 40 years after the man who would become his artistic mentor. Melzi was born into Milanese nobility in Lombardy, Italy, and his superior education included prominent training in the arts. He became da Vinci’s favorite pupil and, although little was written about him, he was fairly well known among da Vinci’s circle of friends.

While the two were both alive, Melzi was known to be da Vinci’s favorite pupil because of his intelligence and talent as a painter. After da Vinci’s death, he became lesser known, despite his dedication to collecting, organizing, and preserving many of da Vinci’s notes on painting and later turning them into a manuscript known as the Codex Urbinas. He also executed da Vinci’s will and cared for his former master’s works, which he yearned to share with the world. He rejoiced in bolstering da Vinci’s name in the annals of time and was content to remain part of da Vinci’s shadow.

Unlike other da Vinci pupils, Melzi’s works included a number of museum-quality paintings and drawings, including the famous red chalk on paper portrait of da Vinci’s profile. Created in 1515, this work was celebrated for depicting da Vinci as classically handsome, even regal. Melzi also completed other famous red chalk drawings, including Head of an Old Man, Vertumnus and Pomona, Five Grotesque Heads, and Seven Caricatures. However, Melzi wasn’t known solely for such chalk drawings; several of his paintings still hang in famous museums today. Among his paintings, the Vertumnus and Pomona—displayed in the Berlin Museum—and Columbina—hanging in the Leningrad Hermitage—were originally attributed to da Vinci, along with several others, reflecting Melzi’s true artistic skill. Although he is still not widely recognized, Melzi’s name is becoming more recognizable in some art circles due to a recent discovery.

Many people have seen copies or renderings of da Vinci’s masterpiece, the Mona Lisa. However, many do not realize that its sister painting currently hangs in Madrid’s Museo del Prado. In recent years, during restoration work, conservators studied the painting using X-ray machines to better understand its background and authenticate its creator. What they found excited them: there was increasing evidence that da Vinci’s star student painted the work around the same time as da Vinci created the original. They even found that Melzi’s changes to the painting coincided with those made by his mentor, contributing to increasing evidence that the two painted these sister masterpieces in close proximity.

However, when studying the restored portrait by Melzi, there are a few distinctions. First, his style isn’t as severe as da Vinci’s; his version is often noted to be brighter, more colorful, happier. In Melzi’s rendering, Mona Lisa’s smile is a little bigger, more mysterious; her eyes call out to the audience a little more energetically. Many Renaissance art scholars feel that, while less popular than da Vinci’s, Melzi’s take is more flattering, albeit less complete, than da Vinci’s. In addition, not just because of where it is displayed, but because of the small, stylistic changes, those scholars feel it’s better able to escape the shadows, proving more accessible to art fans.

Standing among the Renaissance paintings in the Museo del Prado, all eyes are on Melzi’s Mona Lisa. The atmosphere is less hushed than that of the secured original at the Louvre. Patrons appreciate the cheerier space and tone of Melzi’s work. This brighter version is awe- and conversation-inspiring. Museum patrons compare it to the more somber original, remarking on each detail. One examines the faint Tuscan landscape in the background while another points out the detail of the chair in which she sits. A docent comments on the decorated dress neckline and more sculpted eyebrows lacking in the original and the patrons lean in to see it. Now that the truth has been unearthed, Melzi’s place as part of da Vinci’s shadow, part of his lasting contribution toward art, will endure alongside his mentor’s.

In the context of the passage, the depiction of Melzi’s rendering of the Mona Lisa (lines 35–40) primarily serves to:

In Melzi’s rendering, Mona Lisa’s smile is a little bigger , more mysterious; her eyes call out to the audience a little more energetically . Many Renaissance art scholars feel that, while less popular than da Vinci’s, Melzi’s take is more flattering, albeit less complete , than da Vinci’s. In addition, not just because of where it is displayed, but because of the small, stylistic changes, those scholars feel it’s better able to escape the shadows , proving more accessible to art fans .

When asked what a description serves to do (its purpose), summarize the lines and draw a logical conclusion about what they add to the passage.

The specified lines describe Melzi’s rendering (style) of the Mona Lisa as compared with da Vinci’s version. Melzi’s Mona Lisa

Therefore, in the context of the passage, the depiction of Melzi’s rendering of the Mona Lisa (lines 35–40) primarily serves to describe Melzi’s vibrant (lively) and more complimentary style.

(Choice B) These lines do not discuss the energy levels of Melzi and da Vinci.

(Choices C & D) Although these lines discuss Melzi’s art, they do not discuss how it reflected cultural dynamics or common painting styles of the Renaissance.

Things to remember:

Summarize the specified lines and draw a logical conclusion about what they add to the passage when asked what a description does in the context of the passage.

Sometimes the present suddenly catches up with the past, as in 2018, when Kraftwerk won the first Grammy in its long history. Not that the world’s premiere music prize hadn’t already honored the pioneers of electropop. Kraftwerk was recognized for their life’s work in 2014 and the Düsseldorf-based group’s legendary fourth album Autobahn was ushered into the Grammy Hall of Fame just one year later. Still, it would be half a century from when Ralf Hütter and Florian Schneider met and founded Kraftwerk in 1968 before the band won an actual Grammy. The Grammy jury named 3-D The Catalogue the Best Dance/Electronic album of 2018. Kraftwerk prevailed over rivals like Bonobo and Mura Masa, who hadn’t even been born when the boys from Düsseldorf were already making history.

Hütter, born in 1946, his changing lineup of musical collaborators, and their recordings in the legendary Kling Klang studio have certainly made both history and waves over the years. Kraftwerk is undoubtedly Germany’s most important contribution to pop music. Ground-breaking pop music critic, musician, record label founder, and professed Kraftwerk fan Paul Morley has called them “more important, more beautiful, and more influential than the Beatles ever were.”

Some people may be put off by that statement, as the Beatles were far and away the more commercially successful band. But the assertion that Kraftwerk had a greater influence on the evolution of music is not without merit. While the Beatles’ music was influenced by earlier pioneers like Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry, and Carl Perkins, Kraftwerk materialized out of thin air. The band members are considered the godfathers of techno, and their electronic beats have influenced other genres. Unlike many pop bands of their generation, Kraftwerk incorporated synthesizers and other electronic devices into its music, inspiring and influencing musicians and bands like Tangerine Dream, Depeche Mode, David Bowie, New Order, and Rammstein. When other bands were afraid of technology, Kraftwerk embraced it wholeheartedly. And when rap began picking up speed in the early eighties, New York hip-hop pioneer Africa Bambaataa was not the only one mining Kraftwerk’s songs for beats to incorporate into his tracks. A few years later in Detroit, resourceful DJs extracted machinelike rhythms from Kraftwerk’s recordings. Today, the international charts are dominated by techno, rap, and many subgenres; those modern innovators never tire of praising Kraftwerk’s pioneering achievements. Even the mainstream rock band Coldplay outed themselves as Kraftwerk admirers a few years ago when they used a riff from Kraftwerk’s hit Computerlie as the central motif of their hit Talk.

Kraftwerk has long since ceased to be a musical trendsetter, but it has become an institution ; new recordings are rare, but the legacy is managed systematically and competently. With dedication and a great deal of secrecy, Hütter toils away on his own mythology. There are very few interviews, no details from his private life, and only a few carefully staged photos, no collaborations—not even with Michael Jackson, who is said to have expressed interest in collaborating at the height of his fame in the eighties. At the time, Kraftwerk was conducting research on the interface between human existence and modern technology. Visuals, staging and philosophy were just as important as the music, and referencing conceptual art was part of the program. Just the fact that the band incorporated ideas and methods from Dadaism, Constructivism, and Bauhaus would ultimately secure Kraftwerk a place in art history.

Consequently, Kraftwerk increasingly prefers performing at art festivals like the Ars Electronica in Linz (1993) or in museums like the New York Museum of Modern Art (2012) or the Berlin New National Gallery (2015). In the past five years, the band has performed one hundred and twenty-five concerts in thirty countries, primarily in such artistic venues. The concept of Kraftwerk is best expressed in art spaces, and its technological developments have begun to realize the metamorphosis from man to machine that was merely a dream when the band first formed. In the early days, the machinelike beats still emanated from drums and the members performed organ, flute, and violin improvisations. Today, Kraftwerk primarily sends out manikin and robot representatives to produce its electronic music. Hütter recently commented on the band’s evolution: “We’ve just never really taken a look [back] at [our early] albums. Now we incorporate more artwork, so Emil has researched contemporary drawings, graphics, and photographs to go with each re-released album, collections of paintings that we worked with, and drawings that Florian and I did. We took a lot of Polaroids in the early days, which we want to include.” These plans, along with their new iOS app (Kraftwerk Kling Klang Machine), just emphasize that the people behind Kraftwerk have long since been eclipsed by their visual and auditory art, yet this helped them keep with the times more than ever.

The expression “put off” in line 14 most nearly means:

Ground-breaking pop music critic, musician, record label founder and professed Kraftwerk fan Paul Morley has called them “more important, more beautiful, and more influential than the Beatles ever were .”

Some people may be put off by that statement, as the Beatles were far and away the more commercially successful band .

To determine what an expression most nearly means, summarize the surrounding details and use them to draw a logical conclusion.

The surrounding lines note that Paul Morley called Kraftwerk “more important, more beautiful, and more influential” than the Beatles—one of the most successful bands of its time. The author then states that some people might be “put off” by such a claim.

Because people might be confused by the claim that Kraftwerk was more influential than the Beatles, and because confused means “unsettled,” the expression “put off” most nearly means unsettled.

(Choice B) Because one would not likely be “delayed” (postponed or made late) by such a statement, this choice does not fit the context.

(Choice C) The context does not indicate that people would be “released” (allowed to act; removed from an official position) by a statement about Kraftwerk’s success.

(Choice D) The context indicates that someone might be shocked or unsettled by a statement that Kraftwerk was more influential than the Beatles; it does not indicate that people might be “disinterested” by (not concerned with) such a statement.

Things to remember:

When asked what an expression most nearly means, summarize the context and select the most logical answer given those details.

From the creators of the earliest known cave paintings and carvings to twentieth-century practitioners of modern art, humans have tried to grasp the essence of the magnificent now-extinct mammoth—its enormous size, strength, and beauty, and its coexistence with and importance to humans. In 1994, paleontologists working in Channel Islands National Park made the remarkable discovery of a 13,000-year-old pygmy mammoth skeleton on Santa Rosa Island, the most complete collection of its kind in the world. Mammoth discoveries are by no means rare. But the 1994 discovery within Channel Islands National Park was indeed rare: the discovery of the world’s first virtually complete pygmy mammoth skeleton. Exclusive to the California Channel Islands, the pygmy mammoth was probably a small form of the Columbian mammoth found on the mainland. Pygmy mammoths varied from 4.5 to 7 feet high at the shoulders and may have weighed only about 2,000 pounds, compared to the 14-foot tall, 20,000-pound Columbian mammoth. In other respects, they were probably similar, with short fur, a typical mammoth body form, and a relatively large head.

The first remains of these Channel Island “elephants” were reported in 1873. Additional excavations over the years have given a basic understanding of a population of mammoths on the islands that through time became smaller in body size and perished as the Pleistocene Era ended about 12,000 years ago. Paleontological excavations on Santa Rosa Island in the 1920s resulted in the retrieval of a significant collection of a new smaller mammoth species, Mammuthus exilis. Philip Orr of the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History recovered additional mammoth materials during archeological and geological work on the islands during the 1940s and 1950s.

These studies have resulted in the hypothesizing of a fascinating odyssey. It is thought a small group of Columbian mammoths embarked on a journey approximately 30,000 years ago that would eventually result in the development of a new species—the Channel Islands pygmy mammoth. At that time when the sea level was about 300 feet lower, the four northern islands of today’s Channel Islands were a single Ice Age “super island” known as Santarosae. Before the melting of glacial ice, this super island was much closer to the mainland—only six miles at its closest distance. What we see today as the four northern Channel Islands are the visible remains of Santarosae.

But how did the mammoths reach Santarosae? With their snorkel-like trunk and buoyant mass, Asian elephants, similarly equipped living relatives of mammoths, are considered excellent distance swimmers, skilled at crossing water gaps. Documented accounts demonstrate that Asian elephants swim to islands they cannot even see—some up to 23 miles away—guided by the odor of ripening fruit and vegetation. Leaving the heavily grazed mainland behind, Columbian mammoths must have made the swim to Santarosae. Once on the isolated island, the population of mammoths, both large and small, increased. This island balance, known as insular equilibrium, between larger and smaller mammoths slowly disappeared. Researchers think warmer temperatures at the end of the last Ice Age about 12,000 years ago mark the beginning of the end for the large mammoths of Santarosae.

As glaciers and ice sheets melted, sea levels rose, trapping the mammoths on the four northern islands we know today. Eventually, the food supply became scarce as the islands decreased in size. Those mammoths that were smaller and could survive with less food and water were at an advantage, especially in times of seasonal shortages. After 20,000 years of dwindling insular equilibrium, smaller mammoths that required fewer resources completely replaced their larger island relatives. In addition, the absence of predators on the islands also may have contributed to this downsizing: large size was never needed for predator avoidance and defense; big mainland predators did not swim.

After 200,000 years as one of Earth’s most dominant species, all mammoths, which once thrived across Europe, Asia, and North America, became extinct nearly 10,000 years ago. Just what caused the demise of this Pleistocene megafauna is still unknown; nearly thirty years of research and testing have not yet provided an answer that is universally convincing. Nevertheless, the Channel Islands pygmy mammoths have aided in the illumination of evolutionary mysteries. Like the unique pygmy mammoths, the ancestors of the extinct giant mouse, the diminutive island fox, and the giant, bright blue Island Jay responded to their island isolation by becoming new species found nowhere else on earth.

The main idea of the passage is that the Channel Islands are significant mainly because they:

To find why the Channel Islands are significant, examine each paragraph for ideas that refer to the special importance of the islands.

| Paragraph(s) | Details |

| 1 | Presents how mammoths have fascinated people, and Channel Islands National Park was the site of a “remarkable discovery” of a pygmy mammoth skeleton |

| 2 | Describes the discovery of the pygmy mammoth skeleton that “was indeed rare” |

| 3–6 | Summarize the pygmy mammoth studies on the Channel Islands and what they have revealed |

| 7 | Illustrates how the study of Channel Islands pygmy mammoths aids in understanding species development |

Most paragraphs develop ideas about the remarkable rarity of the Channel Islands pygmy mammoth fossils and what they reveal. Therefore, the passage’s main idea is that the islands are significant because they feature fossils that provide evidence for the existence of pygmy mammoths.

(Choice A) The author notes in P7 when all mammoths and other large mammals disappeared, a worldwide occurrence not unique to the Channel Islands.

(Choice C) P6 indicates how islands developed from natural causes. Pygmy mammoth fossils don’t reveal these causes.

(Choice D) P1 and P2 focus on the uniqueness of pygmy mammoth fossils, not Columbian fossils.

Things to remember:

Answers may include an idea mentioned at a single point in the passage, but the main idea of a passage will be developed throughout the passage.

Passage A by Katherine Mansfield

Ah! The train had begun to move; the train was on my side. It swung out of the station, and soon we were passing the vegetable gardens, passing the servants beating carpets of manor homes, passing the gaunt, stray animals prowling among deserted streets with tall blind houses for rent. I was not alone in the carriage; an old widowed woman sat opposite, her frayed skirt turned back over her knees, a threadbare bonnet of black lace on her head. In her fat, calloused hands, adorned with a wedding and two mourning rings, she held a letter. Slowly, slowly she sipped a sentence, and then looked up and out of the window, her lips trembling a little, and then another sentence, and again the old face turned to the light, tasting it … Two soldiers leaned out of the window, their heads nearly touching—one of them was whistling, the other had his coat fastened with some rusty safety-pins. Is there really such a thing as war? Are all these laughing voices really going to the war?

We both gaze out of the windows. What beautiful cemeteries we are passing! They flash brightly in the sun. They seem to be full of cornflowers and poppies and daisies. How can there be so many flowers at this time of year when war rages? But the objects are painful to witness because they are not flowers at all, but rather bunches of ribbons tied on to the soldiers’ graves.

I glanced up and caught the old woman’s eye. She smiled and folded the letter. “It is from my son—the first we have had since October. I am taking it to my daughter-in-law.”

“Is he well?” I asked in genuine concern.

“Yes, very good,” said the old woman, shaking down her skirt and putting her arm through the handle of her basket. “He wants me to send him some handkerchiefs and a piece of stout string.” I smiled, glad for the first time because finally I knew of one family secure in the knowledge that their son, husband, father is alive and comforted by thoughts of his family. For now.

I got up and leaned my arms across the window rail, my feet crossed. What is the name of the station where I have to change? Perhaps I shall never know, so engrossed in my own thoughts.

Passage B by Virginia Woolf

As the carriage made its way, I looked at my fellow passenger, a middle-aged woman whose hair had escaped its pins to lay lifeless around her face. Such a bleak expression of unhappiness was enough by itself to make one’s eyes slide above the newspaper’s edge to the middle-aged woman’s pinched face—insignificant, ordinary without that look, almost a symbol of human destiny with it. Life’s what you see in people’s eyes; life’s what they learn, and, having learnt it, never, though they seek to hide it, cease to be aware of it. The terrible thing about her is that she does nothing at all. She looks at life.

As if she heard my thoughts, she looked up, shifted slightly in her seat and sighed. I glanced at the newspaper in an effort to distance myself, but then my eyes once more crept over the paper’s rim. She shuddered, twitched her arm awkwardly to the middle of her back, and shook her head. You cannot use The Times for protection against such sorrow as hers. The best thing to do against life was to fold the paper so that it made a perfect square, crisp, thick. This done, I glanced up quickly. She gazed into my eyes as if searching for any sediment of sympathy at the depths of them.

So, we rattled through Surrey and across the border into Sussex. The unhappy woman sighed loudly in my direction. I had been glancing out of my window for several moments when I heard her shifting noisily in her seat. Leaning a little forward, she palely and colorlessly addressed me—talked of stations and holidays, of brothers at Eastbourne, and the time of year, which was, I forget now, early or late. But at last looking from the window and seeing, I knew, only life, she breathed, “My sister-in-law.” The bitterness of her tone was like lemon on cold steel, and speaking, not to me, but to herself, she muttered, “Oh, that cow!” She broke off nervously, then she shuddered and made the awkward angular movement that I had seen before, as if some spot between the shoulders burned or itched. Then again, she looked the most unhappy woman in the world.

How do you reply to such a comment? “Sisters-in-law,” I said, hoping to end the conversation. Her lips pursed as if to spit venom at the word; pursed they remained. All she did was to take her glove and rub hard at a spot on the window-pane. She rubbed as if she would rub something out forever—some stain, some indelible contamination. Indeed, the spot remained for all her rubbing, and back she sank with the shudder. Something impelled me to take my glove and rub my window. There, too, was a little speck on the glass that resembled my companion. For all my rubbing it remained. She saw me. A smile flitted and faded from her face. But she had communicated, shared her secret hate, passed her poison, she would speak no more. Leaning back in my corner, shielding my eyes from her eyes, seeing only the slopes and hollows, greys and purples, of the winter’s landscape, I read her message, deciphered her secret, reading it beneath her gaze.

Throughout Passage B, the middle-aged woman’s reaction to the narrator is to:

When asked to identify a character’s reaction to the narrator, locate details describing the character’s behavior or actions toward the narrator.

The loud sighs in the narrator’s direction reveal an “unhappy woman” who seems to be looking for sympathy from the narrator. She communicates to the narrator her “secret hate” for her sister-in-law in an effort to gain her pity. Therefore, the middle-aged woman’s reaction to the narrator is to attempt to elicit (gain) her sympathy.

(Choice B) In P3, the middle-aged woman leans in to the narrator to speak to her, so she does not completely ignore her.

(Choice C) Although the woman seems irritated and unhappy, the details suggest that these emotions are directed toward her sister-in-law and not the narrator.

(Choice D) The details in the passage do not indicate that the woman is surprised by the presence of the narrator.

Things to remember:

Look for details describing a character’s behavior throughout the passage to determine how one character reacts to another.

Planets revolve around a sun-like star that gives off heat and light. However, those suns eventually die, as do the planets around them. Over billions and billions of years, the sun’s core burns hydrogen into helium and expands, increasingly producing radiation that heats up the surrounding solar system. Eventually, the sun runs out of hydrogen and the layers break down, igniting its helium core, and it bloats into a red giant. After approximately 120 million years, it expands outward, consuming any nearby planets, and retracts again as gravity pulls it back. The sun experiences a short-lived rebirth over the next 100 million years until it finally repeats the process of expansion and contraction, like a beating heart. Finally, after another 20 million years or so, it disbands into the atmosphere and leaves the core behind as a white dwarf star. Over time, the white dwarf continues cooling, until the entire solar system disappears.

Scientists have gathered data that shows that “when planets are young, they too glow with infrared light from their formation,” said Michael Jura of UCLA. “But as they get older and cooler, you can’t see them anymore.” However, recently scientists have discovered that, like Carl Sagan hoped he would, the planets might “live again, that some…part…will continue.” In other words, dying planets don’t necessarily just degrade; like the sun, planets too can experience a short-lived rebirth. After billions of years of growing old, a massive planet could, in theory, brighten up with a radiant, youthful glow, “making that rejuvenated planet visible again,” says Jura.

Years ago, astronomers predicted that some massive, Jupiter-like planets might accumulate mass from their dying stars. The dying stars blow winds of material outward that could fall onto giant planets orbiting in the outer reaches of the star’s system. Thus, a giant planet might absorb that material, swell in mass, and heat up due to friction caused by the falling material. This older planet, having cooled off over billions of years, would once again radiate a warm, infrared glow.

Rejuvenated planets, as they are nicknamed, were previously only hypothetical. But new research from NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope has identified one such candidate, seemingly looking billions of years younger than its actual age. Recently, Spitzer detected excess infrared light around the white dwarf, called PG 0010+280. Scientists weren’t sure where the light was coming from, but the circumstances fit the newly theorized rejuvenated planet scenario. After an undergraduate student on the project, Blake Pantoja, then at UCLA, serendipitously discovered this unexpected excess of infrared light around the star while searching through data from NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or WISE, follow-up research was conducted to determine its source.

At first, the team thought the extra infrared light was probably coming from a disk of material around the white dwarf. In the last decade or so, more and more disks around these dead stars have been discovered—around 40 so far. The disks are thought to have formed when asteroids wandered too close to the white dwarfs, becoming chewed up by the white dwarfs’ intense, shearing gravitational forces. Other evidence for white dwarfs shredding asteroids comes from observations of the elements in white dwarfs. White dwarfs should contain only hydrogen and helium in their atmospheres, but researchers have found signs of heavier elements—such as oxygen, magnesium, silicon, and iron—in about 100 systems to date. The elements are thought to be leftover bits of crushed asteroids, polluting the white dwarf atmospheres. But the Spitzer data for the white dwarf PG 0010+280 did not fit well with models for asteroid disks, leading the team to look at other possibilities. Perhaps the infrared light was coming from a companion small “failed” star, called a brown dwarf—or more intriguingly, from a rejuvenated planet.

“I find the most exciting part of this research is that this infrared excess could potentially come from a giant planet, though we need more work to prove it,” said Siyi Xu of UCLA and the European Southern Observatory in Germany. “If confirmed, this theory would directly tell us that some planets could potentially survive the red giant stage of stars and be present around white dwarfs.” Scientists like Xu are understandably excited since further evidence could bring a breakthrough in their understanding of solar system formation and function. In the future, NASA’s upcoming James Webb Space Telescope could possibly help distinguish between a glowing disk or a planet around the dead star, solving the mystery. But for now, the search for rejuvenated planets—much like humanity’s own quest for a fountain of youth—endures.

The first paragraph’s primary purpose is to:

…However, those suns eventually die , as do the planets around them. Over billions and billions of years, the sun’s core burns hydrogen into helium and expands …. Eventually, the sun runs out of hydrogen and the layers break down , igniting its helium core, and it bloats into a red giant . After approximately 120 million years, it expands outward , consuming any nearby planets, and retracts again as gravity pulls it back. The sun experiences a short-lived rebirth over the next 100 million years …. Finally, after another 20 million years or so, it disbands into the atmosphere and leaves the core behind as a white dwarf star ….

To determine the main purpose of a paragraph, note its main ideas and select the answer that addresses the majority of those ideas.

P1 describes the gradual death of a sun as:

Therefore, the first paragraph’s primary purpose is to recount a sun-like star’s process of degeneration (breaking down) from the beginning through the white dwarf phase.

(Choice A) Although P1 states that “suns eventually die, as do the planets around them,” this is the only discussion of planets; their life span is not mentioned.

(Choice B) P1 mentions that “the sun experiences a short-lived rebirth over the next 100 million years,” but it does not reveal how this happens; in addition, only a small portion of the paragraph addresses this possibility, so it cannot be the main idea.

(Choice C) P1 does not mention the Spitzer Space Telescope.

Things to remember:

Summarize the main ideas and select the answer that addresses most of them when asked the main purpose of a paragraph.